The Gift

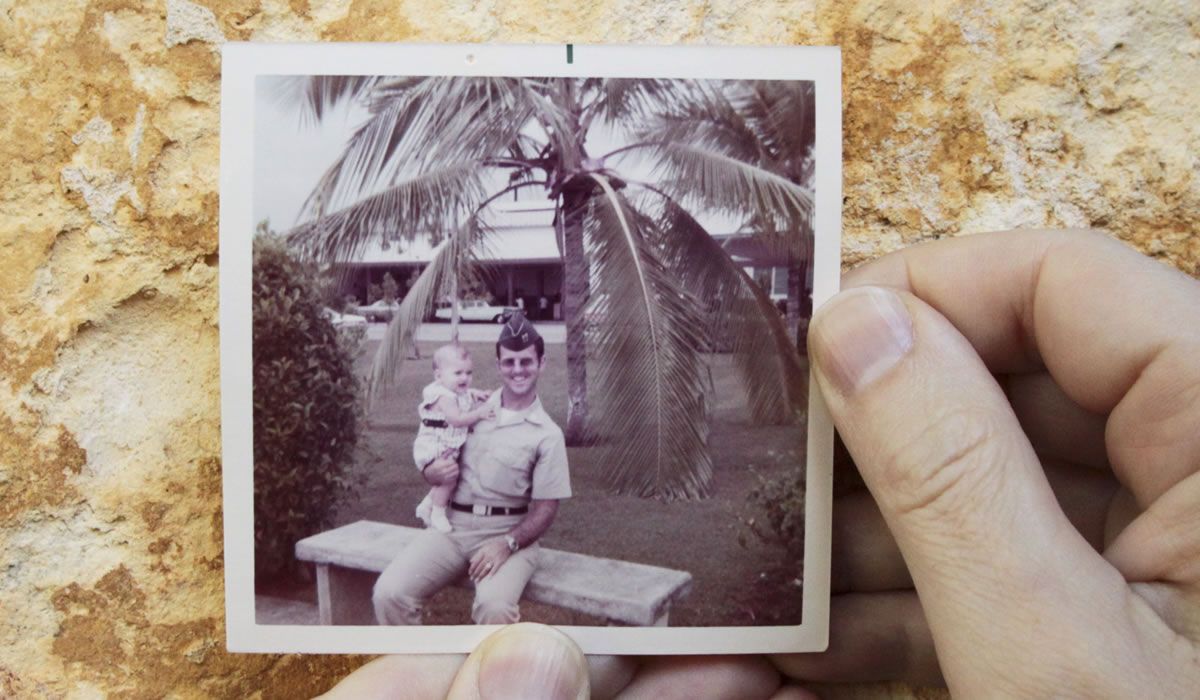

My thoughts on suicide, assisted suicide, dignity with death, Robin Williams, Brittany Maynard, and my dad Michael Semegran

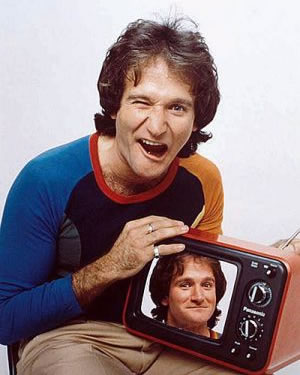

I have been thinking about my father a lot lately, more than usual, because of two controversial topics I have read about in the media this past year: suicide and assisted suicide. What initially prompted me to think more about my dad was Robin Williams' suicide on August 11, 2014. Having such a high profile person commit suicide definitely put the spotlight on this topic even though suicides claim the lives of tens of thousands of people every year and is the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S. (CDC). My father, Michael Semegran, committed suicide on December 4, 2002. He was not a famous person, he was just my dad. Robin Williams and my dad had a LOT in common which was what got me thinking about my dad so much. I'll get to that in a bit; now to assisted suicide. Brittany Maynard committed assisted suicide on November 1, 2014. Maynard was diagnosed with a stage 4 malignant brain tumor. She moved with her family to Oregon so she could legally kill herself with lethal medication prescribed under the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. She definitely put a new face on this topic since she was young and attractive and very vocal on social media about her path to death with dignity. What is the difference between a family member who commits suicide and a family member who commits assisted suicide? There is a very fine line between dignity and shame on the way to the same end, apparently. I find that to be very strange and perplexing and hurtful.

I have been thinking about my father a lot lately, more than usual, because of two controversial topics I have read about in the media this past year: suicide and assisted suicide. What initially prompted me to think more about my dad was Robin Williams' suicide on August 11, 2014. Having such a high profile person commit suicide definitely put the spotlight on this topic even though suicides claim the lives of tens of thousands of people every year and is the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S. (CDC). My father, Michael Semegran, committed suicide on December 4, 2002. He was not a famous person, he was just my dad. Robin Williams and my dad had a LOT in common which was what got me thinking about my dad so much. I'll get to that in a bit; now to assisted suicide. Brittany Maynard committed assisted suicide on November 1, 2014. Maynard was diagnosed with a stage 4 malignant brain tumor. She moved with her family to Oregon so she could legally kill herself with lethal medication prescribed under the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. She definitely put a new face on this topic since she was young and attractive and very vocal on social media about her path to death with dignity. What is the difference between a family member who commits suicide and a family member who commits assisted suicide? There is a very fine line between dignity and shame on the way to the same end, apparently. I find that to be very strange and perplexing and hurtful.

When Robin Williams committed suicide, I was shocked--if only for a few minutes--and it seemed the world was shocked as well. How could someone so universally loved and admired do such a thing as commit suicide? By all accounts, he was a very successful and brilliant man, actor, and comedian. He starred in several universally acclaimed movies such as Good Morning, Vietnam, Dead Poets Society, Awakenings, The Fisher King, Aladdin, and Good Will Hunting. He was a unique stand-up comedian who intimidated his contemporaries, many considered great in their own right. He earned an Oscar, two Emmy Awards, six Golden Globe Awards, two Screen Actors Guild Awards, and five Grammy Awards. And he made millions of dollars doing all of this. My father was also brilliant and successful although on a different, more down-to-earth scale. He earned both Bachelors and Masters Degrees in Industrial Engineering. He had a decorated, 25-year career in the Air Force leading a team programming computer software. He was called a genius by his commanders and way ahead of his time. He retired from the Air Force and made six figures working as the Director of Tech Support at Ashton-Tate, one of the "Big Three" software companies of the 1980s, which included Microsoft and Lotus. By all measures, both my dad and Robin Williams were successful men and geniuses.

They had other similar traits. On a lighter note, both men were short and stocky with an abundance of body hair. But it was also clear to me that, despite their success, both men suffered from depression and mental illness although they dealt with that reality in very different ways. Robin Williams was very vocal about his issues with depression and substance abuse. His comedic routines contained tons of personal fodder and he was quoted as saying that using his troubles as material was "cheaper than therapy." My father, on the other hand, never spoke a word to my mother, my sister, or me about his diagnosis of depression by Air Force doctors during routine, annual check-ups. It wasn't something we learned about until my mom found the paperwork in his military files long after the funeral. Why is it that successful men can contemplate taking their own lives and follow through with it? How can a successful extrovert and a successful introvert both follow the same path to their early demise?

It took years of therapy to help me move forward from debilitating thoughts related to my father, our prickly relationship, and the manner of his death. Unlike Robin Williams' children--Zelda, Zachary, and Cody--my family and I were able to grieve and cope in private without prying media pundits, nasty social media commentary, and the opinions of everybody in THE WORLD. My heart breaks for Robin Williams' children. They have a long road to recovery ahead, one that unfortunately never ends in Happyville. Almost twelve years later, I'm still traumatized by my father's suicide although I have been able to reconcile my feelings about him. Knowing what I went through to cope and heal, the most difficult thing for me when reading opinions in articles, watching news clips on television, and reading comments on social media websites about Robin Williams' suicide was knowing that most everything they said about suicide was wrong, that their focus was all wrong. 'How could someone who had everything do that?' they said. 'How could he do such a selfish thing to his family?' they said. These were obvious questions with unhelpful answers. Their responses wouldn't help you understand suicide one bit. I knew that if they really wanted to understand suicide then they were asking the wrong questions.

Years of therapy told me this but there was also a bigger problem: our attitude as a society towards suicide. Do we really care enough to ask the right questions? If the question is "Why did he commit suicide?" then the answer is "Mental Illness." Simple. Unfortunately, most states and our country do not put mental illness on their priority lists. Funding for mental health services and programs are routinely slashed, dropping by 23 percent in Texas alone in recent years. Also, when it comes to our collective moral stance toward suicide, it is looked upon with shame and intolerance, particularly in Christian churches, who view suicide as a grave sin. 'How dare someone take their own life, which is a gift?' they say. The modern Catholic Church has lightened its stance on suicide as a sin because someone who commits suicide may not always be fully right in their mind and thus not one-hundred-percent morally culpable. That does not erase centuries of condemnation, though, from the church. And what about those who are not mentally ill but are terminally ill?

Brittany Maynard didn't have a mental illness. She had a brain tumor. When she was 29, she was diagnosed with a stage 4 malignant brain tumor but soon realized, "After months of research, my family and I reached a heartbreaking conclusion: There is no treatment that would save my life, and the recommended treatments would have destroyed the time I had left," she said. After some research, she discovered death with dignity. It is an end-of-life option for mentally competent, terminally ill patients with a prognosis of six months or less to live. She and her husband uprooted from California to Oregon, one of only five states where death with dignity is authorized. After establishing residency, she received a prescription from a physician for medication that she could ingest to end her "dying process" when it became unbearable for her. Why did she choose this method? According to Brittany, "It has given me a sense of peace during a tumultuous time that otherwise would be dominated by fear, uncertainty and pain." She died surrounded by her loved ones on November 1, 2014.

Brittany Maynard didn't have a mental illness. She had a brain tumor. When she was 29, she was diagnosed with a stage 4 malignant brain tumor but soon realized, "After months of research, my family and I reached a heartbreaking conclusion: There is no treatment that would save my life, and the recommended treatments would have destroyed the time I had left," she said. After some research, she discovered death with dignity. It is an end-of-life option for mentally competent, terminally ill patients with a prognosis of six months or less to live. She and her husband uprooted from California to Oregon, one of only five states where death with dignity is authorized. After establishing residency, she received a prescription from a physician for medication that she could ingest to end her "dying process" when it became unbearable for her. Why did she choose this method? According to Brittany, "It has given me a sense of peace during a tumultuous time that otherwise would be dominated by fear, uncertainty and pain." She died surrounded by her loved ones on November 1, 2014.

The Death with Dignity Movement has been growing in the U.S. for some time in recent years. As I mentioned, five states now have laws permitting death with dignity and the list will be growing as other states honor the requests of their constituents to allow them the option to die with dignity. But where does that leave the rest of us who had family members who committed suicide? Why is it OK for someone with a terminal disease to "die with dignity" but someone with a severe mental illness or depression cannot? It's a difficult topic to dissect but from what I've read from family members who have loved ones who have died with dignity, they all say the same thing: it was a gift. They say it was a gift because they were given closure with their loved one, something that family members of people who commit suicide do not get for the most part. I didn't get closure with my father and neither did my sister or my mother. To be certain, Brittany's gift to her loved ones was closure. But for me, 12 years after my dad's suicide, I have learned that my dad's gift to me was empathy and compassion for him and others with mental illness and depression. I miss my dad very much and know that I will never have closure with him about why he chose to commit suicide but I now have the empathy to understand the suffering that all of us are susceptible to inside.

The main reason most look down upon suicide and assisted suicide and why the church considers it the gravest of sins is because they call life a gift. This is an undeniable truth. But, for the sake of argument, if life is a gift, then a person should be able to do with it as they please. To not be able to do with life as one pleases is like being given a present from a loved one but then being given stipulations on what to do with it. In this case, it's not really a gift at all but a burden. Or, as another example, it would be like going to a party and being told that you must have fun, no matter what, even if you don't find the party to be fun. And also, whether you are having fun or not, you cannot leave until they say you can leave, even if you just want to go home before the party ends. In other words, your personal freedom to do what you want with your gift or to spend the time you want at the party is not yours to make. If life is a gift, then it can also not be a gift. In fact, sometimes life can be unbearably hard. People do not choose to have mental illness. Sometimes, there are things to help people cope and sometimes they don't work. People do not choose to get cancer. Sometimes, it can be cured and sometimes it's terminal. As humans, we must have the right to choose how we live our lives. If that is true, then we must have the right to choose how we end our lives, if need be. No matter what, we must find the empathy and compassion to respect what people choose. Life is beautiful and life is hard. Who is anyone to judge anyone else for how life has treated them?

As for my father, I do not know why he made the choice to commit suicide but I do know this. He suffered through years of terrible back pain from spinal surgeries that did not fix his back problems and neck pain from fused vertebrae. Excruciating pain is very difficult to live with. My family and I believe he suffered from depression and may have been bipolar. After being laid off from his last high-paying job, he was never able to find work again at the level he was accustomed to, something he felt was a result of ageism and very bad luck. In the last year of his life, he was reduced to applying for work at his credit union or Home Depot. My father was a brilliant, proud man. I am certain the physical pain he suffered and the depression he hid so well both took their toll on him. My family wishes we could have helped him, if only we had known. But, and I say this with a heavy heart, even Robin Williams seeked help from support groups. He was actively participating in rehab and on medication. We don't know why our loved ones chose to end their lives the way they did. It still makes me cry thinking about my dad and Robin Williams and I didn't even know Robin Williams. I do know what his family is going through.

About a month after Robin Williams passed away, my wife and I decided to watch The Bird Cage with our four children. It is not considered the best Robin Williams movie of his career but I knew it would certainly make our kids laugh. Boy, did it ever! We were all laughing throughout the movie and singing "We Are Family" at the end while the characters escaped their imprisonment from the throng of reporters outside the nightclub. I know that Robin Williams, my dad, and Brittany Maynard have escaped their prisons, too. Everyone deserves dignity with their death.